Keeping time at the Moon

AUTHORS: PHILIP LINDEN AND ASHLEY KOSAK

A new approach to lunar timekeeping—built from affordable commercial hardware, redundant clock networks, and shared open infrastructure.

Illustration of ESA’s Moonlight navigation satellites operating in lunar orbit. Image: Thales Alenia Space / Briot

Three, two, one. Go!

The year is 2035. The first literal space race has begun—a competition for the fastest travel time between Earth's North Pole and the Lunar South Pole. Competitors from all sides of the space community are set up to have a go: from government-run space agencies carrying the pride of their nations, to university students with boundless ambition; from scrappy startups proving their name to megacorporations looking to "show the rookies how it's done"; even decentralized organizations pushing the limits of what the internet's collective intelligence can achieve.

This race is a time trial. Competitors launch from Earth in succession so everyone runs their own race against the clock. The race directors manage super sensitive instrumentation at either end.

Ashley's launch pad in Svalbard starts two timers at the exact moment a ship leaves the ground. One of the timers stays with Ashley at race control on Earth while the other is along for the ride. Phil has prepared a landing pad near the Moon’s Shackleton Crater that detects the exact moment a spaceship touches down. Phil has a timer too, set up with laser communications to Ashley's. The launch pad sends the landing pad a signal to start Phil's timer at the start, and the landing pad sends a "stop" signal back to Ashley's timer at the end. Can't take chances when every nanosecond counts.

A loudspeaker blares over the crowd that has gathered at Svalbard station. "And they're off! MoonDAO's crowd-funded spaceship is on its way to the Moon! Brought to you by Open Lunar Foundation, The Lunar Ledger, and viewers like you..."

While the spaceships in this story are impressive, our stars Philip and Ashley face the most difficult challenge: keeping accurate time from Earth to the Moon.

There are a number of challenges when it comes to measuring time. While the story above might be fictional, it exemplifies real problems that spacecraft operators face. Clock accuracy is critical for every packet of data and command sent between Earth and lunar spacecraft to ensure reliable operations, and to avoid orbital collisions. The story continues…

"Ship's a quarter arcsecond off the target vector. Ryan, you think we can course correct?" Pablo calls to his crewmate aboard 2 The Moon, MoonDAO's second spacecraft prototype to reach orbit. Pablo taps the time display nervously. One second can't be this long, can it? Must be the adrenaline.

"Executing a burn for 0.8 meters-per-second delta vee a few milliseconds after perigee. All systems nominal," Ryan replies.

Moments later, the thrusters briefly ignite. Lights on the control panel glow a reassuring green as Earth diminishes in the viewport on the bridge. The crew floats with bated breath for a few minutes, all eyes glued to the clock silently advancing second by second. Telemetry, navigation data, and computer logs light up and reflect brightly across Ryan's glasses. "Okay, nobody panic..." Pablo locks eyes with his copilot in dread and understanding.

The atomic clock at the heart of _2 The Moon_'s navigation system was salvaged from the 2025 Time Card student project, entering the line of duty in lieu of a newer clock that was destroyed in the first flight test. During pre-flight checks, MoonDAO's chronometer was precise enough to measure down to 500 nanosecond increments and the Chip Scale Atomic Clock was up to spec, especially when it could sync with GNSS. The in-flight display shows the same sub-microsecond accuracy. Yet the ship's trajectory prediction flickers and drifts whenever the GNSS signal drops.

A couple hundred nanoseconds, that's it. We'll be fine, Ryan tells himself. But the CSAC isn't the only one with uncertainty right now.

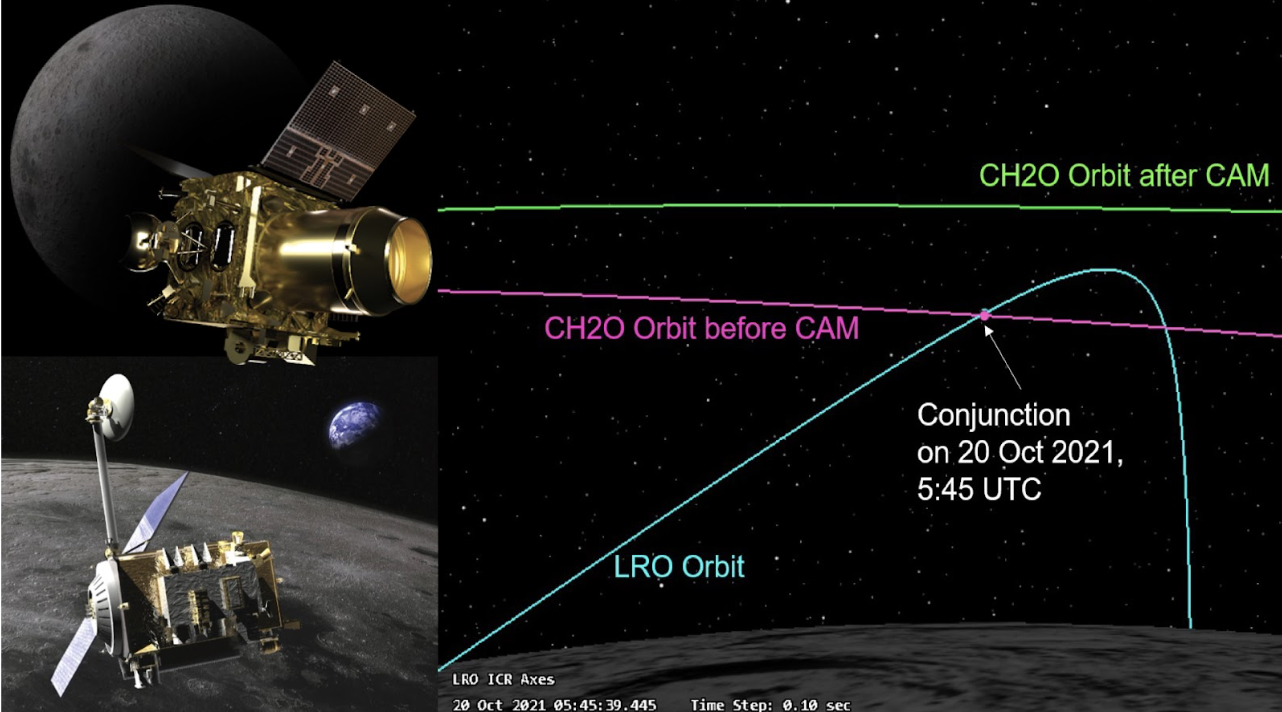

Left: Illustrations of the ISRO Chandrayaan 2 and NASA LRO orbiters around the Moon; Right: Increase in separation between their orbits after Chandrayaan 2 performed a diversion maneuver. Images: ISRO / NASA / GSFC / Chris Meaney

This science fiction scenario of a clock ticking faster than expected happens with actual satellites. For navigation and mission planning, just hundreds of nanoseconds in timing error corresponds to kilometers of inaccuracy in trajectories of spacecraft. Precision is the primary challenge for lunar operators today. Unlike terrestrial or near-Earth applications, lunar operators don’t have the luxury of receiving a highly accurate and stable time signal from the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS), commonly called GPS. Dependence on GNSS is mission-critical for rendezvous or proximity operations in low-Earth orbit (LEO)—and even the driving directions we rely on everyday here on Earth. When you need to coordinate multiple spacecraft the same way you do in Earth orbit but at the Moon, discrepancies between different time systems of each satellite increase collision risk while decreasing effectiveness of mutual operations and goals.

Earthbound GNSS satellites are equipped with Rubidium Frequency Standards to keep time with utmost precision, which cost millions of dollars. Even so, GNSS satellites experience clock drift, due to technology limitations and Einstein’s postulated and now-proven relativistic effects. Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) and International Atomic Time (TAI) are internationally recognized as the "official Earth time." GNSS satellite constellations orbit Earth at altitudes between 20,000-36,000 kilometers at speeds of over 14,000 kilometers/hour. The speed and distance make their onboard clocks tick at a different rate than terrestrial clocks. Because the Moon is more than 10 times farther away, these effects get more pronounced, leading to more clock drift. With a few operational spacecraft, manually coordinating timekeeping differences is feasible, which is what space agencies currently do like the case of NASA, ISRO, and KARI orbiters avoiding collisions with each other. But when we have more and more spacecraft operating on and around the Moon in the near future, especially as missions converge at the water-hosting south pole, they will face unique challenges in synchronizing their clocks and keeping errors in check. The costs for such systems needing to be precise will escalate.

On the other hand, the sheer costs of precision clocks also necessitate engineering tradeoff. NASA's Deep Space Atomic Clock (DSAC) mission, for example, cost almost $100 million, including development, the cost of the clock itself, and mission operations. Quotes for a GNSS-grade clock alone can be as high as $2 million. On the other hand, the kind of crystal oscillator you might find in an alarm clock costs the manufacturer pennies in bulk.

For lunar missions, the balance between accuracy and cost requires some middle ground. In fact, there is a broad set of clock technologies that might be "good enough" for a lunar mission in the $50-5000 range. In 2025, Open Lunar Foundation, in partnership with MoonDAO, sponsored six engineering students at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) to develop a clock for a lunar CubeSat with a budget of just $10,000. Called the “Time Card” project, it resulted in a working prototype, demonstrating a functional time card using a Chip-Scale Atomic Clock (CSAC) from Microchip donated by MoonDAO. The total cost of the project—including the Chip-Scale Atomic Clock—came to $6,055.

The Time Card prototype demonstrates that commercial-off-the-shelf-technology can achieve "good enough" timekeeping at a fraction of the cost of the tried-and-true exquisite clocks that we’ve relied on for the last 50 years. And CSACs aren’t even the only low-cost and low-power oscillators on the market. Beyond individual accuracy, there are also advantages to operating multiple clocks together; by averaging their readings, we can create a more stable and precise measure of time.

An example of a commoditized precision time telling approach for the Moon, wherein clocks adjust frequency to match its neighbours, little by little. Actors close to each other will be more tightly synchronized as compared to actors far away. Image: Philip Linden et al., Open Lunar

This work arrives at a critical moment. The next wave of lunar exploration will not be a handful of isolated missions but an overlapping ecosystem of landers, rovers, orbiters, and commercial & infrastructure services operating side by side. These missions will need a trustworthy, mission agnostic sense of time—a coordinated lunar time to schedule landings, maintain safe distances, manage power and data relays, and authenticate navigation signals in places where GNSS cannot reach. Establishing that shared foundation is essential for the Moon to function as a true multi-operator environment.

To that end, we are excited to launch Epoch, the newest chapter in Open Lunar’s timekeeping research. Our goal is to build a shared lunar time standard, an open source system that lets students, developers, and industry experts coordinate even where GNSS cannot reach, from the depths of the ocean to the orbit of the Moon.

Our motivation: Meet the demands of an accelerating lunar ecosystem by building low-cost shared infrastructure. These efforts are directly complementary and feed into initiatives by space agencies worldwide. NASA is coordinating with US government stakeholders, partners, and international standards organizations to establish a lunar time standard calculated independently of Earth. ESA targets launching a constellation of five satellites called Moonlight to provide lunar navigation signals and communications (navcom) to hardware at the Moon’s south pole.

The story continues…

Phil waits patiently at the finish line, stargazing from his lawn chair planted in the regolith while the racers hurdle toward him from tens of thousands of kilometers away. He glances at the array of timers on the scoreboard. A hard expression forms on his face, an expression not so different from the technology skeptics back home. With a sigh, Phil adjusts the thermal controller on his suit to something cozy. He leans back in the chair, once again staring into the black. "It’ll be fine, right?"