Moon missions need their own Wikipedia and beyond. Open Lunar is building it.

Open Lunar Foundation is building the Lunar Registry, a community platform to share information about Moon missions as well as privately coordinate orbital traffic to reduce collision risks and build trust between competing entities.

Our Moon may be one of the largest satellites in the Solar System but its exploration has been concentrated on select areas. One of these is low lunar orbit, where mapping spacecraft from three countries have been concurrently flying from pole to pole between 50 to 150 kilometers above the Moon’s surface for three years. These are the US’ Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), India’s Chandrayaan 2 orbiter, and South Korea’s KPLO spacecraft. The Moon’s gravity being uneven means they operate in select orbital planes to maintain their mapping orbits and avoid crashing into the Moon. But that also means their orbits often overlap, increasing the chances of these orbiters running into each other at high velocities.

Left: Illustrations of the ISRO Chandrayaan 2 and NASA LRO orbiters around the Moon; Right: Increase in separation between their orbits after Chandrayaan 2 performed a diversion maneuver. Images: ISRO / NASA / GSFC / Chris Meaney

The situation has compelled their three space agencies—NASA, ISRO, and KARI—to coordinate and share precise trajectory information of the lunar satellites with each other, and even conduct diversion maneuvers to avoid uncomfortably close passes. Last July at the Secure World Foundation’s Summit for Space Sustainability, a KARI researcher presented how the three agencies are using NASA’s MADCAP software to predict and alert operators of potential close approaches between the orbiters, after which a decision can be taken for either craft to divert.

In October 2021, ISRO commanded the Chandrayaan 2 orbiter to slightly change its orbit to avoid a three-kilometer close approach to NASA’s LRO. Similarly, LRO postponed a maneuver in 2023 to avoid more such close conjunctions. An August 2023 blog post by ISRO specifically on the importance of managing growing lunar traffic mentioned the Chandrayaan 2 orbiter maneuvering to avoid close approaches to KPLO. In turn, KPLO too has performed multiple such maneuvers. These will only grow in number in the coming years as more reconnaissance orbiters become operational amid increasing Moon missions worldwide.

Slide from KARI’s presentation at SWF’s Summit for Space Sustainability in July 2024. Credit: Moon-Jin Jeon of KARI, who leads KPLO mission operations

Enter the Registry

Unfortunately, these largely manual coordination efforts from NASA, ISRO, and KARI can’t scale adequately for future exploration—given that there’s no global lunar traffic management system agreed upon or in place. Even spacecraft briefly passing by lunar orbit on their way to the Moon’s surface can trigger alarms. Last year, KPLO avoided a close approach to Japan’s SLIM spacecraft before the latter’s Moon landing. The decision had to be taken within a day. The risks of cascading accidental collisions within the tight orbital mapping spaces our Moon’s gravity allows is increasing.

“If you announce a launch date, you should publish trajectory information”, says Mehak Sarang, Director of Industry Integration at the Open Lunar Foundation. Sarang has experience working on Moon missions, having last worked at ispace-US, a subsidiary of ispace Japan building a lunar lander with US-based Draper to carry scientific payloads for NASA’s CLPS program.

If all organizations operating at the Moon could securely access trajectory information of others in sufficient detail at a trusted node, it would not only reduce collision risks for everyone but also save on complex operational and analysis costs. It’s to this end that the Open Lunar Foundation is building the Lunar Registry, an accessible platform and database of public as well as appropriately private information on Moon missions worldwide. “Commercial actors could better benefit from sharing trajectory information”, says Sam Jardine, who leads stakeholder engagement for the Lunar Registry.

During the initial scoping of what such a lunar registry needs to account for, Open Lunar learnt that creating the Registry would be more a political challenge than a technical one. To that end, Jardine engaged over 150 government, industry, civil society, and scientific stakeholders last year through one-on-ones and workshops to gather valuable feedback and gauge their interests. This included hosting events on the sidelines of the International Astronautical Congress 2024, and participating in the 2024 UN Conference on Space Law and Policy. A common takeaway was that information sharing is widely considered to be critical for effective governance at the Moon. Stakeholders are keen on a UN-aligned global registry created by an apolitical NGO—since that would invite the least objection globally. That’s why the Open Lunar Registry aims to operate as a non-profit which transparently collects an objective set of mission information.

A page from history

“The reality of space is that it’s very polarized”, says Rachel Williams, Acting Executive Director of Open Lunar. Information flow and exchange about missions navigates complex political and national security blockers like with US export controls. Moreover, it doesn’t help that intellectual property is currently not protected in space. The competitive landscape further discourages information sharing even for mission aspects that aren’t sensitive. To that end, the Registry will encourage and incentivize collecting information that can indeed be shared for the benefit of all.

“Having a third party, neutral, independent organization transparently handling mission information will benefit all actors across safety, cost, and trust,” notes Williams. There’s also precedent in the space industry for this. Shortly after the advent of the Space Age, the UN Registration Convention required countries to provide basic information about objects being launched to space. It helped reduce tensions during the Cold War—especially to avoid misassumptions about rocket launches and their not-always-present military intentions. Said registry continues in operation today, although the UN recognizes challenges with getting sufficient levels of information in the registry as global space activity compounds.

Likewise, the Antarctic Treaty System—though considered imperfect by all involved—has resolved many challenges for decades. The bottomline is that trust enabled by transparency decreases political escalation and conflict. Other than lunar orbit, such transparency will also be needed on the Moon’s south pole, a region of convergence and potential contest for future missions to access water ice and other resources. If the unintended impact on the Moon’s farside by a likely defunct Chinese spacecraft in 2022 had been near the south pole instead with active missions or astronauts in the future, it would’ve triggered major alarms.

A rocket body impacted the Moon’s farside on March 4, 2022, creating a 28-meter long double crater. Image: NASA / LROC / GSFC / ASU

The crescent of trust

Despite the prohibitive Wolf Amendment, NASA recently successfully sought a US Congressional exception to allow US scientists to apply to study valuable Moon samples brought by China’s Chang’e missions to Earth. While we wait for its fruits to bear, two US universities have already gotten selected to study Chang’e 5 samples in their labs with self funding. Such scientifically beneficial, low-risk environments present opportunities to build elements of collaboration and trust. It also sets better norms to constrain the depths and divisions of political competition while yielding better trust in future activities—something especially important when building something as complex as a Moonbase. It’s that element of trust building in opportunistic environments that Open Lunar aims to facilitate with the Lunar Registry.

A panorama from the Chang’e 6 lander on the Moon’s farside, showing one of its legs and the scoop sampling arm near its surface digs. Image: CNSA / CLEP

A successful registry will include private and national missions, the former group especially benefiting from the safety and visibility perks of participating in the Registry. Open Lunar has already tested Registry Prototypes with over 100 users across various organizations, and is gearing up for a public release later this year.

“Our goal is to build trust with the first group of users by making them see the value, which can then lead to a snowball effect,” says Williams. “Due to competition in CLPS and lack of incentive, the market also lacks credible information about potential customers and competitors”, says Sarang. But with a trusted registry, “it could be lucrative to punch yourself in, even if just to find potential customers”.

“It could be a way to incentivize more commercial companies to share their landing site areas if not coordinates,” added Jardine. The core challenge here would be to “nail down the minimum number of core mandated fields,” so that every public mission page in the Registry comes with assured benefits for all while simultaneously allowing the next layer of information to be private as appropriate.

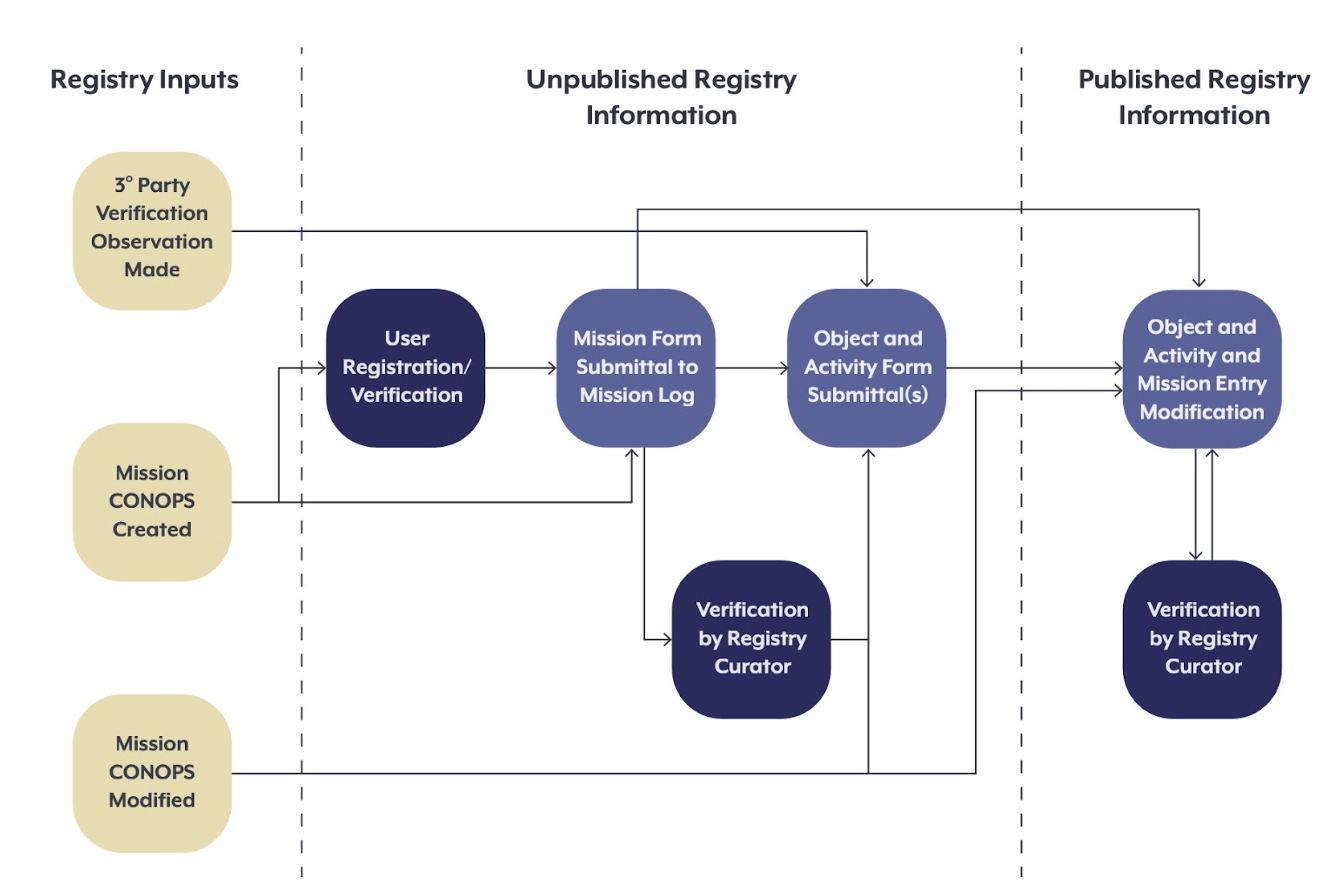

A basic visualization of the Open Lunar Registry’s process flow

Wikipedia for the Moon

Involving space enthusiasts around the world is also the Lunar Registry’s key goal. Community-oriented works the likes of CelesTrak and Jonathan’s Space Reports are well known for providing uniquely useful and reliable information about space missions for public benefit. With the Registry, we have an opportunity to pool such credible utilities in one place for all things lunar exploration globally. The Registry can thus enable community verification while adequately delineating information and its sources as coming from either mission operators or community volunteers.

Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer as well as creator of the aforementioned Jonathan’s Space Reports, is an advisor for the Lunar Registry. McDowell has stressed the importance of multi-stakeholder-reported data verification: “With all registries, traceability is trust. Retaining original information is crucial in building a registry, but allowing a complementary verifiable mechanism is key.” The lead of the Lunar Registry Christine Tiballi said, “We'll need to develop data standards so that we end up with harmonized inputs & outputs in ways that don’t stifle interest from different stakeholders.”

The Registry’s operations will be paired with a multi-stakeholder advisory group, a process known to increase engagement and cooperation through inclusiveness. In fact, the internet’s own open registry is an excellent example. The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), an international non-profit managing the global domain name system (DNS), has successfully implemented a multi-stakeholder model by having governments, businesses, technical communities, and civil society participate in the decision-making processes.

A Registry that allows space enthusiasts and organizations worldwide to contribute information and review its credibility can help everyone better explore and track past, active, and future Moon missions from across the globe. Wikipedia is perhaps the best demonstration of the power of collective public knowledge banks. “Having a Wikipedia style community of enthusiastic contributors, curators, and editors would be fantastic”, remarks Jardine.

Looking ahead, the Registry would advance Open Lunar’s own mission to promote cooperative and peaceful exploration of our Moon based on equitable technical and policy building blocks. “It allows us to see and think deeply about interoperability from multiple mission and program perspectives”, notes Sarang.