Open Lunar’s Origin Story

Authors: Rachel Williams, Chelsea Robinson

It’s 2018.

We’re sitting in an industrial office in San Francisco’s SOMA district, surrounded by space agency executives, astronauts, CEOs, lunar scientists, and engineers. Laptops and snacks cover the massive table, along with pages of handwritten notes and diagrams.

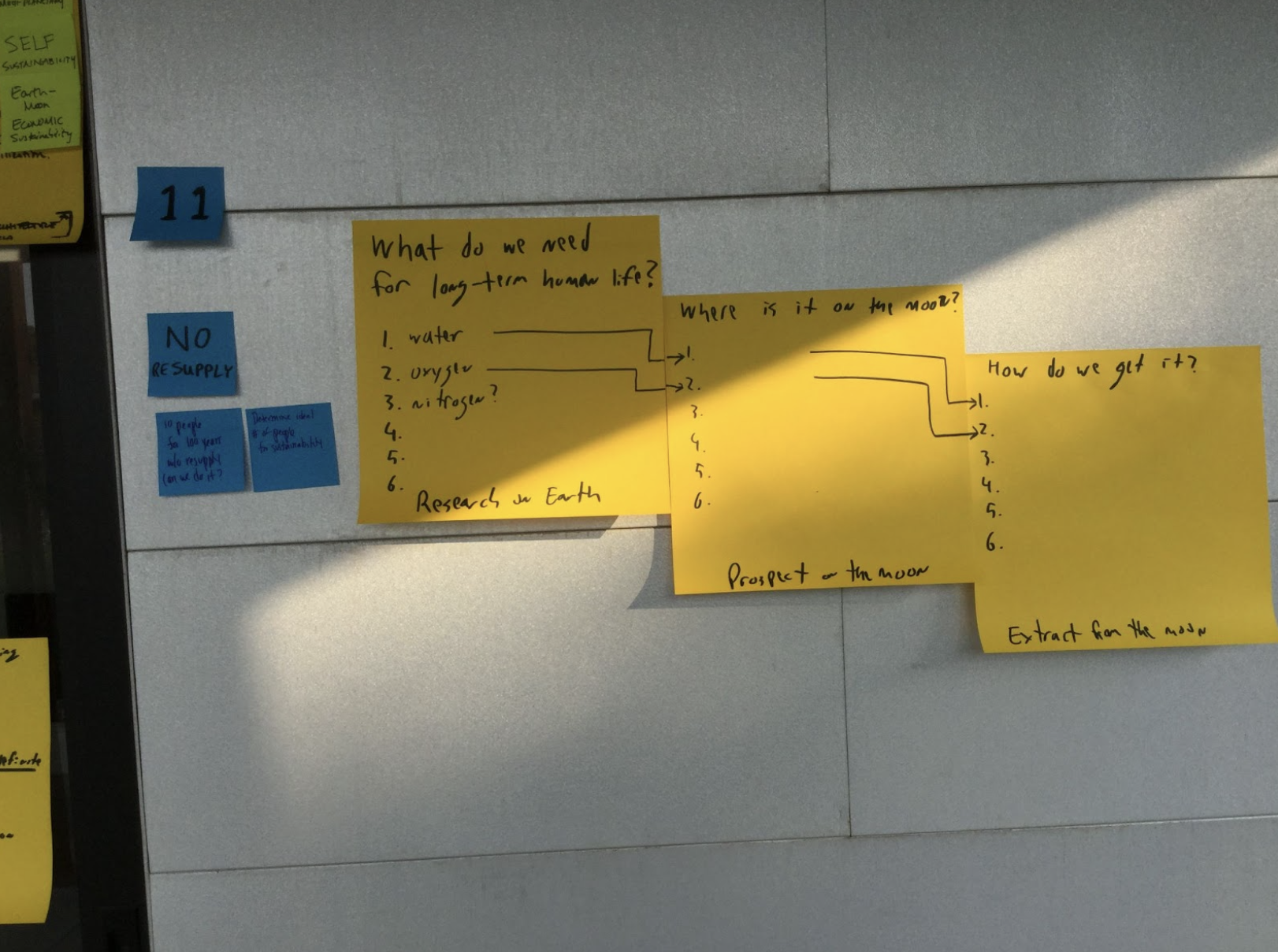

An Open Lunar ideation brainstorm on what long-term human presence could really mean: sustaining 10 people on the Moon for 100 years, without resupply.

We’re talking about lunar dust mitigation from landings and its damage to other machinery. The ground-truth data we desperately need on water ice in permanently shadowed regions. The propulsion gaps holding small spacecraft back from translunar injection. And most critically, the tension between those envisioning lunar mining and those advocating for untouched lunar research parks.

In 2018 space faring nations and companies were reprioritising lunar missions. The Google Lunar XPRIZE had sparked a crop of commercial ventures, yet the prize itself ended in 2018 without a winner. NASA had just unveiled CLPS and began shaping Gateway, ispace landed major venture funding, and bold announcements were abundant, and tens of millions of funding were pouring into each mission from new and unlikely sources. Most critically, the cost of launch had come down by a factor of ten and lunar insertion prop and nav was gaining TRL rapidly. Moon shots were gearing up everywhere, and despite classic schedule slips and a high failure rate (space is hard), the sector was powering up for active pursuit of lunar settlement.

Chris Hadfield, Open Lunar Board Chair, and Robbie Schingler, Open Lunar founding member and donor; co-founder of Planet Labs discussing Open Lunar’s Innovation Process.

One of our founders, Robbie Schingler, called it “a lunar renaissance", while at the same time, the dangers of an unregulated, uncoordinated environment were becoming clear. National licensing schemes were emerging in isolation, companies were announcing missions without sharing data, and speculation of mining profits surged ahead of basic prospecting or science. Governance was fragmenting as each national program defined their own interpretations of the Outer Space Treaty’s edge cases, while the commercial sector frantically competed for access to funds, payload partners, and credibility but when asked about precedent setting considerations they had no comment.

Soon, incidents showed the implications of what this meant in practice. An unannounced rocket booster impacted the lunar far side with no ownership claimed. Close approaches in cislunar space between independent missions revealed the absence of shared tracking or collision-avoidance norms. As payloads from a growing number of actors began reaching the lunar surface, the risks became even more tangible. India’s Chandrayaan-2 lander crashed near the lunar south pole. SpaceIL’s Beresheet mission drew global attention when it failed on landing—raising unexpected questions about payload contents and biological contamination. Many more missions were already manifested to fly, prompting urgent conversations about risk, responsibility, and long-term stewardship.

These moments made clear that humanity was returning to the Moon without a shared playbook. The industry was receiving sharp signals that coordination, communication, and collective thinking were no longer optional for a sustainable and peaceful future on the Moon.

Open Lunar was coming together rapidly.

Our community of over 120 seasoned mission experts, policy makers, engineers and legal minds were meeting regularly to define a contribution. Some of us were motivated by the dream of becoming an interplanetary species, others by the possibility of applying space governance models to reshape institutions back on Earth, and still others by the promise of new markets and economic opportunity. Yet, we all shared a common commitment: if humanity is to succeed on the Moon, we cannot repeat the patterns of rampant exploitation, geopolitical rivalry, ‘growth at all costs’ and militarization that have defined our history. We must build together, and openly, if we want a different outcome.

And so emerged Open Lunar: a nonprofit founded by a global community -- some of the field’s most experienced and visionary minds. Open Lunar is dedicated to ensuring that when humanity returns to the Moon, we do so in a way we can be proud of.

From the start, we asked ourselves: what can a small, values-driven nonprofit contribute to setting wise precedents and accelerating a shared future on the Moon?

Our answer is to build the utilities and public goods that make lunar stewardship real. By establishing vital infrastructure that supports all missions and drives coordination, we set the foundation for how the Moon will be governed from day one. We invest in infrastructure like lunar data registries, coordinated landing pads, resource management frameworks, open standards, and accountability systems. We are not only solving technical challenges, we are also making sure that shared human values shape the foundation of lunar activity.

In 2018, our global team worked in monthly sprints to research, debate, and evaluate potential infrastructure projects. World-class experts came together to ideate, stress test, and refine our early vision for lunar governance through practical utilities. Open Lunar incorporated and mobilized with a full staff and office to develop technical hardware to influence the next waves of lunar exploration.

From the outset, Open Lunar had a portfolio of efforts. We were working on small landers, long-term settlement frameworks, a gap analysis on ISRU science, and critical payload identification needed to prove or disprove uncertainties about lunar conditions, and policy/ legal analysis of ownership, governance and norms.

Open Lunar Community

The lander work was inspired by Planet Labs (planet.com) to use an agile ‘new space’ approach to deep space missions, just as they did for LEO. We defined a “lander series” for flying multiple tiny lunar modules. Our aim was to fly multiple landers, and demonstrate the advantages of shipping quick cheap small spacecraft (10M and two years per mission, opposed to 100M and 10 years per lunar mission).

Working on hardware inhouse was a means to an end. We aimed to enhance coordination and get faster outcomes through collaboration. It became clear that working alongside the ecosystem of lander companies and teams would be more aligned with our long term goals. We found that our niche was in catalysing the shared utilities that would connect the lander and payload ecosystem of actors.

We assessed our broad base of projects, and tightened our RnD process focussing on those which best met our impact criteria. We have maintained the new space mindset, and we fund project scopes iteratively to maximise learning.

Through this process, some of our earliest work evolved into our strongest current projects. We started out creating a Settlement Traceability Matrix to assess the gaps in tech and science for human settlement in 2018. By 2019 this had evolved into a project called the Lunar Open Architecture (LOA), which sought to map transparently all the work happening in the sector towards settlement and highlight the opportunities for support or action. In recent years this work has been reshaped into the creation of the Lunar Ledger, a public registry of all lunar activity for lunar actors to benefit from as a utility.

It’s 2026

Today we carry forward an active, expert-vetted, and well-resourced portfolio of projects, aimed at addressing the same early problems we saw emerging: repeated mission failures with little information sharing, geopolitical blocs impeding global cooperation, commercial companies racing ahead of governments, and governments leaning on those companies to shape regulation. De facto rules are being set in real time, conjunction events threaten missions even in a not-so-crowded cislunar space, and unregulated mining and extraction plans are planning to move forward without guardrails. With projects we’ve created, incubated, and funded like Lunar Designated Areas, Moon Dialogues, Lunar Policy Handbook, Breaking Ground Trust and Lunar Policy Platform, we are actively moving to solve these challenges.

We believe in a future where the Moon is more than our nearest celestial neighbour.

It is deeply connected to our home planet and serves as the staging ground for deep space exploration across our solar system. Here, governance and precedent will be tested in ways that ripple outward to asteroids, Mars, and back toward Earth. Open Lunar’s work has never been only about the Moon. It is about shaping humanity’s relationship with itself. The projects we incubate today are stepping stones toward a future where governance is collaborative, transparent, and inclusive — on the Moon, and back here on Earth.